By Étienne Fortier-Dubois

This essay first appeared on Étienne Fortier-Dubois’s personal blog.

You’re sitting in a math class in university. The professor is writing a proof on the blackboard.

You’re extremely focused. The logic is spelled out with perfect clarity. Each step makes sense.

Then, the instructor utters a word-perhaps “obviously” or “trivially”-and proceeds to write the last line of the proof.

You blink once.

Twice.

You read the result a couple of times. You frown. It doesn’t make sense anymore. Something happened between the last two lines of the proof, but you have no idea what.

This proof wasn’t obvious to you. It certainly wasn’t trivial. You glance around, and to your relief, you see you’re not alone. Your classmates keep silent, but they look confused too.

The instructor has overestimated the obviousness of the proof.

And so does everyone, all the time, with everything.

What does it mean for a piece of information to be obvious?

It really just means that the piece of info is known. Once you learn that the sky is blue, or that the Earth is round, or that the longest-lived human was a 122-year-old French woman, then these facts sound obvious to you. No one can impress you by telling you these things anymore.

Since most things aren’t known by most people, universally obvious facts are rare. The only true candidates are probably very basic facts about human biology and the natural world, such as “I can see stuff only if I open my eyes.”

For everything else, obviousness is a function of the audience.

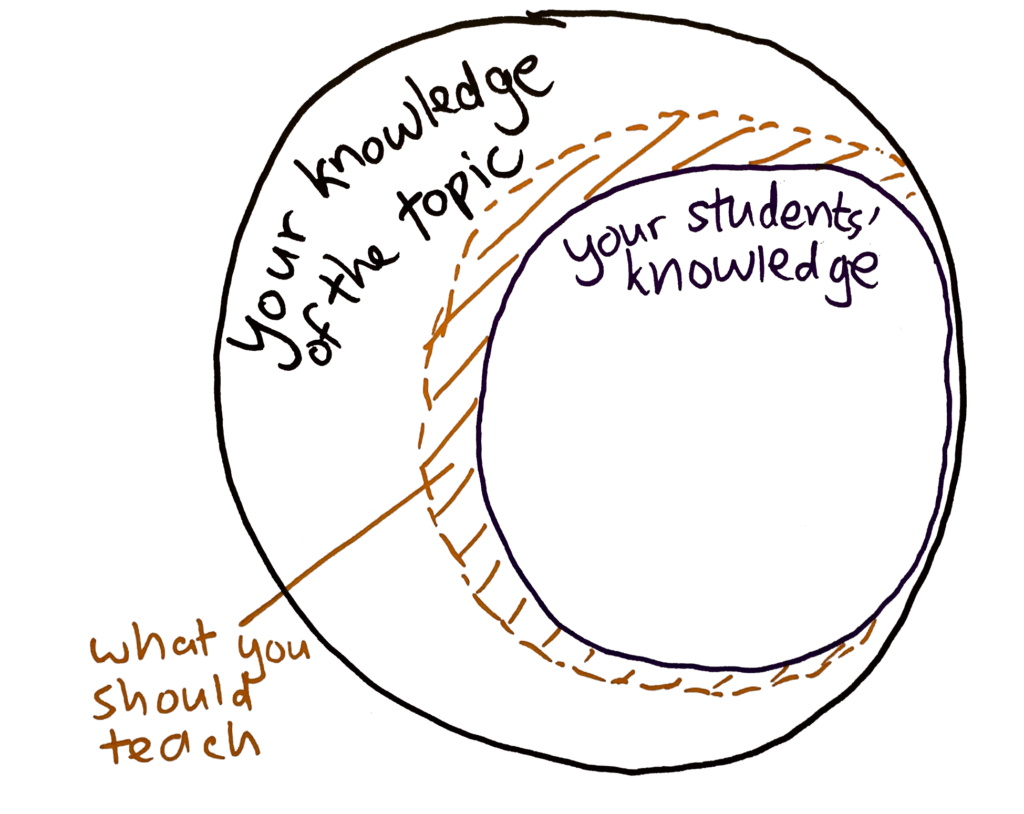

If you’re a math teacher at a university, you can consider “2 > 1” to be obvious. Your students know this. But some more advanced concepts won’t be that obvious to them. Since by definition you know more math than your students, many things will sound more obvious to you than to them.

To a large extent, it is your job to be aware of the gap between your students’ knowledge and your own, so that you can pick the right things to teach. It can’t be too obvious, or it’ll be boring. And it can’t rely too much on non-obvious other things, or it’ll be confusing.

To do this, you need to estimate your audience’s knowledge. Fortunately for you as a hypothetical math teacher, that’s not too hard in the context of a classroom. Standardized tests and prerequisite coursework are your allies here. Misreadings can happen, like in the math proof example, but the system is tuned to minimize them.

Now let’s generalize to the larger group of people who publicly express facts and opinions — writers, journalists, podcasters, social media users, youtubers, and other communicators. We’ll take writers as an example.

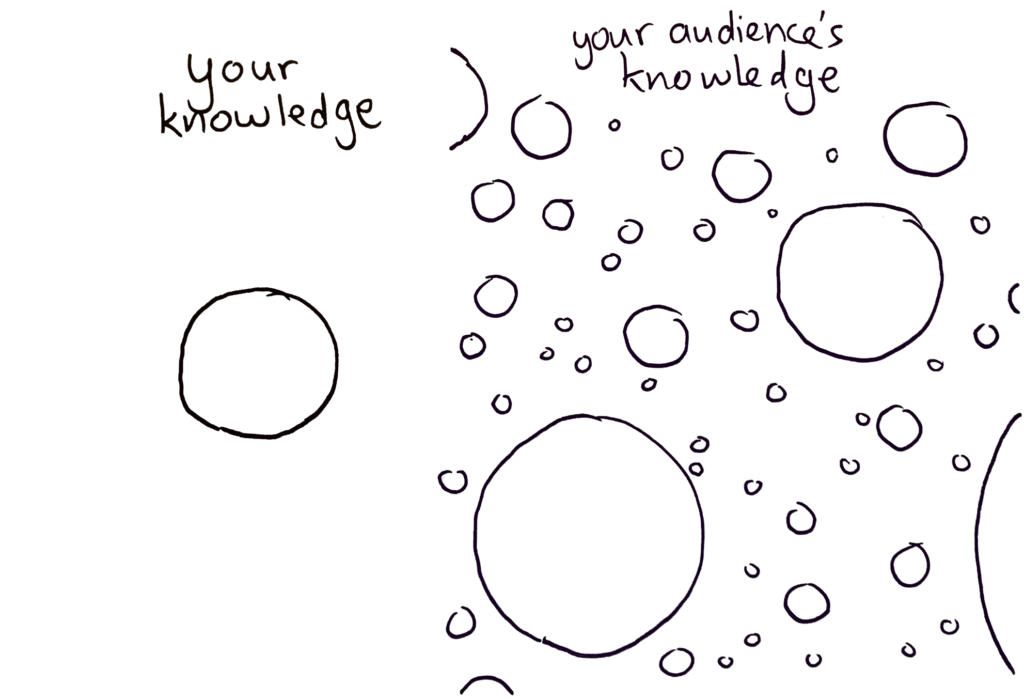

In most cases, your audience as a writer is less easy to characterize as it is for a teacher. Even if you write about a very niche topic, you’re likely to be read by both novices and experts. And if your work is less specialized, or more widely distributed, estimating your audience’s knowledge gets even harder. At worst, all you know is that they can read your language.

And when you can’t get a precise estimate, you start worrying.

You might worry about confusing your audience, if you’re trying to explain a complicated point. But another common task of writers is to find interesting things to say. In that context, the danger from overestimating obviousness changes: the risk is that you (incorrectly) decide that an idea isn’t interesting enough for you to write about.

This is something I’m often concerned with. Whenever I have an interesting fact or idea to share, I’ll have thoughts along the lines of: “This is obviously true. Why am I wasting my and my readers’ time writing about it?”

Just writing this down makes it painfully obvious that it’s wrong. It’s healthy to put efforts into making sure that your writing is worthy of being read, of course. But it’s also easy to err on the side of worrying too much. Of never saying anything interesting, because you’re afraid it’ll be obvious and boring.

Perhaps not every writer needs to worry about this. Maybe your problem is that you underestimate obviousness, say lots of things that are self-evident to your readers, and should consider shutting up a little.

But I think overestimation is a more widespread problem than underestimation. The reason is simple: often, the main evidence we have about other people’s knowledge is just our own knowledge. Psychology has a word for this: projection bias. We tend to project onto others and assume they are more similar to us than they truly are.

I struggle with this. So I’ve been coming up with rules to help me deal with it.

1. If you’ve never heard anyone say it, and you can’t find anything when you google it, and you share it with a professor in the relevant field and they say, “wow, I’ve never thought of this before,” then it’s not obvious

Congratulations! You’ve generated a new idea. This is extremely rare. Quick, write a paper, book, or blog post before someone else comes up with it.

2. If you’re hesitating about whether it’s obvious, then it’s not obvious

If it were obvious, you’d obviously know, wouldn’t you?

Well, not necessarily. I can come up with a contrived counterexample. Imagine that everyone in your audience has seen a tweet which you haven’t. You happen to write about the same idea, believing it’s a mind-blowing insight, and… turns out it isn’t. It was obvious to everyone, but you couldn’t know that.

Since these situations are probably very rare, I claim that my heuristic is useful.

3. If you were excited enough to write about it, then it’s not obvious

If you took the time to write something, you must have thought it was interesting. Chances are that others will, too. So, as you hover above the “Publish” button, wondering if you were really just stating the obvious, I’m here to tell you, “Click. Just click the button.”

4. If you learned it by following your own curiosity, or doing something special, then it’s not obvious

Everything you know, you had to learn.

If you learned something by following your interests, perhaps going down a Wikipedia rabbit hole, or a YouTube spiral, then it’s likely that others haven’t. If you’ve learned it doing something that most people haven’t done, like work at a super secret company or travel to Kyrgyzstan, then you can be fairly sure lots of people don’t know about that.

Either way, you’re qualified to share the knowledge with the world.

5. If you’re learning it right now, then it’s not obvious

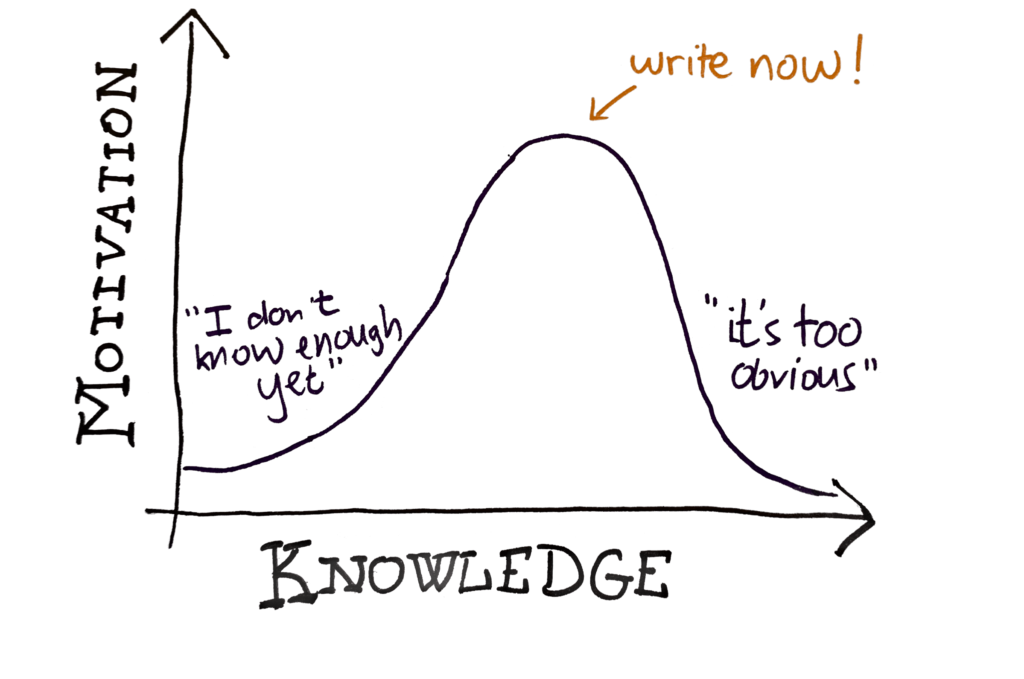

There was a picture I saw on Twitter, but which I can’t find anymore. I’ll try to reproduce it from memory:

When you know a lot, a topic may sound obvious and boring to you. When you know very little, you won’t feel qualified. In both cases, you won’t be inclined to write about it.

The ideal is to hit the sweet spot in the middle. Guessing where you are on the curve is not easy, but a simple trick is to share as you learn. As soon as you feel you know enough, write about it, before you reach the right side of the peak. It’s almost guaranteed that many people are just to your left, and will enjoy being brought along.

6. If it sounds obvious but you’re combining it in a non-obvious way, then it’s not obvious

Here are two obvious statements:

- Whales are mammals.

- Milk can be used to make cheese.

We combine these two statements, and voilà, we get something much less obvious: cheese made from whale milk is a thing (or, at any rate, a theoretical possibility). I don’t know about you, but I have literally never thought of whale cheese until I came up with this example.

Thus the common, but true, advice: it’s far easier to combine existing ideas than to generate new ones. Everything is a remix.

Note that the rule also applies to combining an obvious idea with a non-obvious one. The beauty here is that the non-obvious idea can be as simple as some personal story. “Love hurts” is obvious to most, but we still enjoy stories that combine it with personal details.

The real reason I wrote this essay is to deal with my own insecurity.

The next time I worry I’m writing something obvious, like the importance of friendship or the complicated origin of cakes, I’ll tell myself, “No, see, nothing is actually inherently obvious. It all depends on the audience, and you’re probably overestimating what your audience knows. So go for it!”

I’ll get it wrong sometimes, but that’s better than preventing everyone from learning something because I wrongly assumed they knew.

Even now, at the end if this essay, I have a nagging feeling that all of the above is obvious. I know it isn’t! But feel free to provide me with additional supportive evidence, if you’ve learned a thing or two from it.