Originally posted by Shahid H N on his substack, shahid’s riffs

This post is inspired by and riffs on Joe Lonsdale’s piece on dialectical wisdom.

Between “self-accountability”…

For most of my adult life, my self-growth came from being somewhat hard on myself. My self-talk said, “Work hard, make every moment valuable. You have so much potential, but you’re not living up to it. Think about all the big dreams you had for yourself when you were younger – why aren’t you any closer to achieving them? You could be so much better!”.

And it worked! I was driven and motivated. I pushed myself, and reaped the rewards for it. Throughout my college years, this attitude got me through tough classes, helped me do well at extracurriculars, and set me up for a decent career and life ahead.

… and “self-acceptance”

But a couple of years ago, I started feeling like I was in a massive rut. It seemed like there was a mismatch between where I wanted to be in many aspects of life (career, relationships, health, wealth), and where I was then. My self-talk hadn’t changed, but despite that I somehow wasn’t actually doing much to improve my situation. So I thought to myself, “Well, being hard on yourself isn’t leading anywhere worthwhile anyway, might as well give this ‘self-acceptance’ thing a try, right?”

I started acting on what I mistakenly thought “living in the moment” looked like: indulgently focusing on short-term pleasure, in an almost hedonistic way. I figured that by “choosing happiness”, I would build up positive energy to channel towards great things. But instead, I felt… nothing. I didn’t achieve anything of value, nor did I feel much better about myself.

Was I doomed to a life where any good I was to ever achieve would have to come from self-flagellation?

On the dialectic

Opposing truths at extremes

Often we come across two opposing ways of doing something that both seem to have their merits. The apparent tension I described earlier between self-accountability and self-acceptance is an example (spoiler alert: I was doing both wrong), but there are plenty others.

So do we have to “pick” a side and lose the merits of whatever the opposite viewpoint is? Or do we have to walk the precarious middle ground between both sides, and only get a portion of the merits that each side offers? Well, neither!

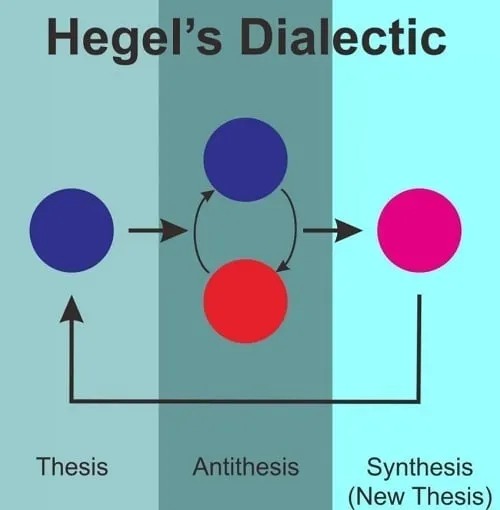

“Dialectic” is a broad term, but here I refer to it mainly in the sense of: a process through which opposing ideas or forces (thesis and antithesis) clash, examine their own internal contradictions, and ultimately lead to the emergence of a new, higher synthesis.

I will borrow from Joe Lonsdale’s elaboration here:

This is what I mean by a “dialectic”, where the truth exists at different extremes and the actual truth is a complex interaction between an initial understanding and its negation. The idea is that most polarizing viewpoints, whether practical or theoretical, contain within themselves apparent contradictions which seem to drive one to the opposite pole. But much as a Zen master appreciates both sides of a koan, one should strive to recognize that two contradicting extremes can often be simultaneously valid.

Many people are sloppy thinkers, and opt for “middle of the road” positions when faced with two opposing extremes. But compromise is often even less accurate than the extreme poles of a dialectic. In my experience, it’s common that deep truths exist at both extremes of a dialectic, and the wisest stance on an issue will incorporate “both of the opposites within itself”.

— Joe Lonsdale, Dialectical Wisdom

When two viewpoints seem to be in contradiction to each other, very often value exists at both extremes. The synthesis of the two, where a higher level of truth integrates both opposites, may not be intelligible at its full resolution yet. But till then, finding a way to hold on to both opposing viewpoints simultaneously can be very powerful!

Be okay with contradictions

Some people are uncomfortable with the notion that you can hold two opposing viewpoints at the same time. To them, consistency is paramount. They spend years building out a densely-connected web of beliefs, and any counterpoint to their worldview is rejected unless it can be integrated into this web.

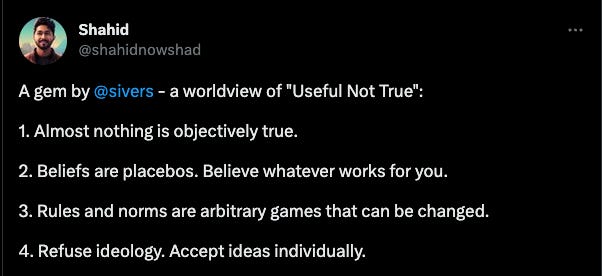

To them (and really, to the me of the past), I say: Guess what? No belief system is wholly coherent! Yes, to some extent we all desire to believe what is true (whatever that really means). But the quest to understand the underlying nature of reality, while a noble endeavor, is also a lifelong one – in fact, you’ll probably get closer to the larger truth by being able to sit with contradictory lower-level truths for a while. In the meantime, make use of what makes sense for a particular moment. “Useful” matters a lot more than “true”.

Epistemic humility is one of the highest virtues.

Dialectic Juggling 101

Recently, I’ve been trying to take a dialectical approach to the accountability-acceptance conflict: take these two opposing modalities, find ways to hold onto them both, and just… see what happens.

I do this mainly by time-boxing each modality socially: I make sure to dedicate some time in the week for people who encourage and challenge me to be better, as well as some time for people who center me and remind me to be thankful for the present. Mimetic desire (the notion that people tend to imitate the wishes and aspirations of other people), is a powerful thing – might as well leverage it.

Sounds obvious? Maybe! But I maintain that if you’re not sure how to hold on to opposing viewpoints simultaneously, committing a certain amount of attention to each and regularly moving between them is a decent start. The social dimension is a major one across which you can perform this juggling act, but there are others: the content you consume, the questions you keep in mind when you journal or do other mindfulness practices, the environments you inhabit… and many more.

My synthesis attempt

I’d like to think that embracing the dialectic between naive self-accountability and naive self-acceptance helped me realize how I was doing both wrong, and perhaps brought me a few steps closer to the holy grail of self-love.

I don’t yet have a very clear vision of what this synthesis looks like. But if I were able to go back in time and meet my younger self, here’s what I would say to him:

Positive > negative encouragement

Instead of a place of fear and despair, pushing yourself to be better can come from a place of curiosity and excitement too! Instead of thinking “I’m screwed if I don’t do this, so I’d better”, think “I’m happy I made it this far, and I can’t wait to see how much further I can go”. Negative encouragement is sometimes needed for a short-term push, but positive encouragement is often more sustainable in the long run.

Play hard, play hard

My Twitter friend Reddy probably has a ton to say on this. For now I’ll just say… forget the grindset, embrace the “play-set”. The desire to live a meaningful life often seems like a consequential and scary undertaking – but it needn’t be. Embrace a sense of play: lean into what excites you, let that positive energy drive you to explore and build, love the process, and distance yourself from the outcome.

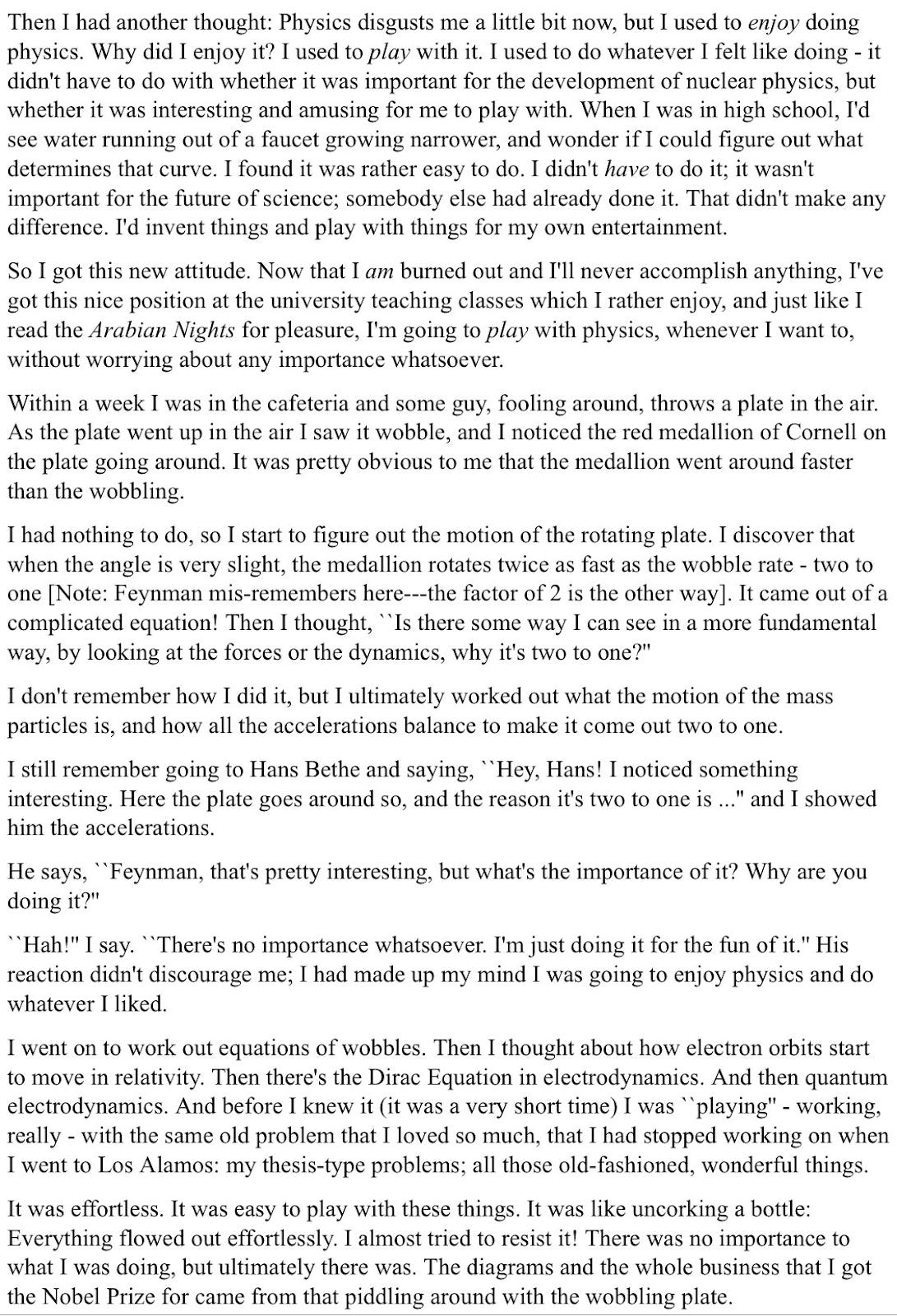

Success needn’t be serious! I remember how struck I was the first time I read this anecdote from Richard Feynman, by way of Visa:

Enjoyability coexists with meaningfulness

Though good rest is essential to good play, playfulness doesn’t mean laziness or indulgence. Self-acceptance includes all parts of you: the parts that derive joy from having the freedom to unwind after a busy day, or from a mindless night with friends… as well as the parts that want to acquire knowledge about the world, and do well in career, and make money. By not honoring all parts of yourself fully, you’re not truly practicing self-acceptance.

Interestingness exists at the intersection of enjoyability and meaningfulness – embrace what feels interesting, not banally enjoyable!

The good news is that “enjoyable + meaningful” is often right next to “mindlessly enjoyable”. A personal example: Watching reruns of my favorite sitcoms is sometimes how I veg out (pleasantly surprised I could quote Webster and not UrbanDictionary here), and the enjoyment that comes from it is certainly mindless. But watching something I haven’t watched before is probably better for me – my brain goes down different paths and generates new ideas, or I learn something new, or at least I get the benefit of staying tuned in to popular culture. Else, watching reruns but with friends to share laughs and make memories with is worthwhile too!

Coda

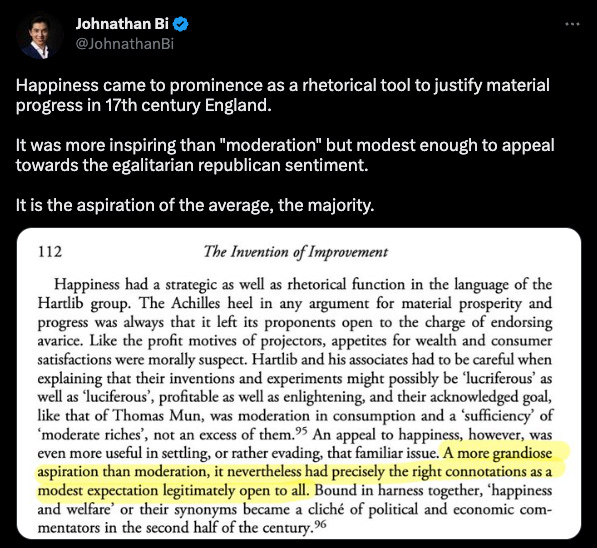

The 50-50 approach to the dialectic may not always work best. Depending on the season of life you’re in, you might want to lean into one side more. Personally, I know I need to actively keep in mind that true joy and fulfillment often comes from denying myself short-term pleasures. A focus on “happiness” tends to get misdirected and lead to behavior that slows down my growth. So as I go through a transitional stage of life, I would probably do better to prioritize the accountability side of the dialectic a little.

But now I have a much more measured and integrated view of what self-accountability looks like, and I’m better protected against the failure mode I was stuck in before.

So if you feel like you’re stuck between two compelling ideas, or philosophies, or ways of doing something… don’t pick one, don’t pick the middle ground, pick both.

Huge thanks to my friends @missrachelreads, Cage, and Maggie for reading drafts of this.