Please enjoy this post “You Do Not Know That Artist You Love” by writer Celeste Marcus, who is currently working on the first English language biography of Chaïm Soutine.

Happy Reading!

—ii Editorial

P.S. Join Celeste in her upcoming salon, “Excavating Man from Myth: Chaïm Soutine and the Cultural Power of Apocrypha” on December 11th!

Great paintings seem somehow vivified. They appear to move or to breathe — if not in the way that living creatures do, then at least in some confounding fashion given that they are wholly static.

This power cannot be taught in art school, though the artists who can confer it must also possess the technical disciplines which are the fruits of academic training. Those artists who are technically accomplished but who lack this higher, mysterious capacity are, then, merely virtuosic. Their skill is much easier to recognize, to describe, critique, place in a context, and to learn from. It accounts for the complexity of the composition, the uniformity of light, the relations between the objects, and how the picture plane is filled. Every stroke that makes up the work is the result of a choice, and a critic or a student of art can, with the proper training, interrogate those choices. But the higher power is thrillingly elusive. It defies characterization since it operates in a realm outside reason, stubbornly defying articulation. Velasquez studied the human form so assiduously that his hand could trace the curve in a woman’s shoulder blade and back with exquisite precision, but no training could have infused those gentle curves with the illusion of flushed life.

Studying a particular oeuvre allows a viewer to develop an understanding of how these two elements — discipline and vivacity (which perhaps map on to Jed Perl’s Authority and Freedom dialectic) — exercise influence upon the artist over time. Each painting is at once an expression of a particular artist’s ever-evolving relationship with paint and an intrinsically fulfilled work unto itself. But this is very difficult for viewers to remember since, if an artist has risen to even a moderate degree of fame, she has probably been reduced to a single work in the cultural imagination. The qualities which make an artist great are not the qualities for which an artist is generally remembered. Once a name has become recognizable to non-enthusiasts, it has often been diluted and converted into a brand.

So, in an attempt to make the artists we love fuller and more human, what follows are a few works with which you might already be familiar, followed by works by the same artist that may surprise you:

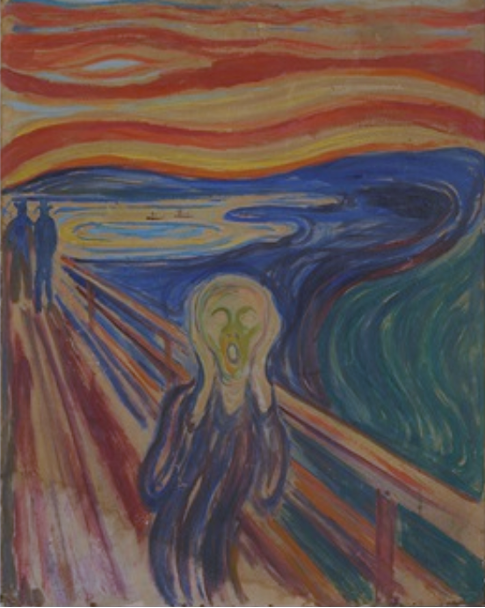

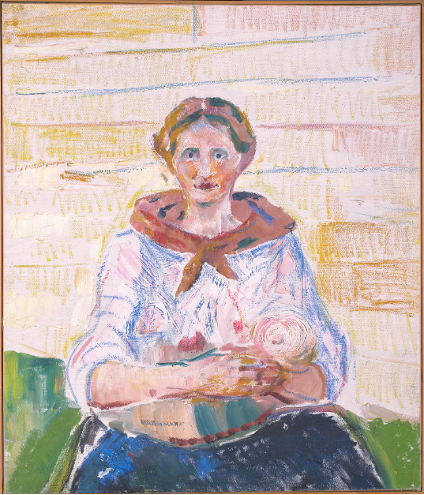

Edward Munch

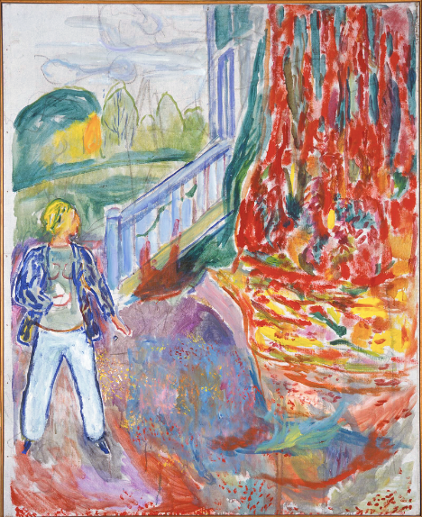

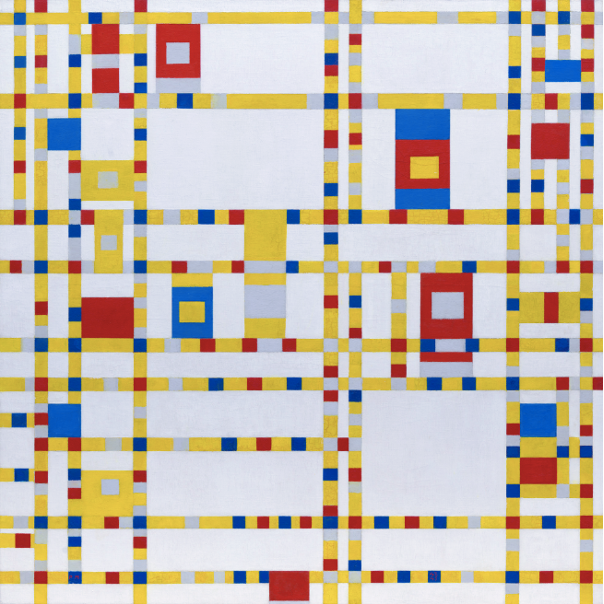

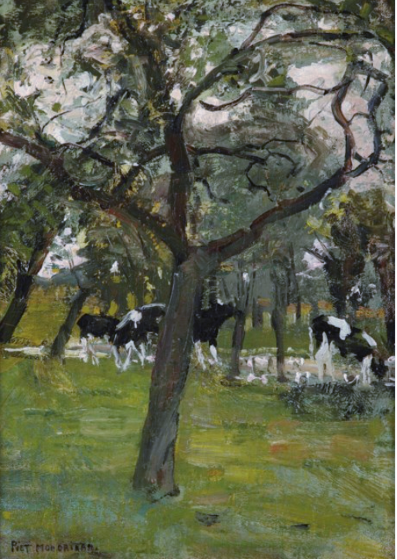

Piet Mondrian

MOMA collection

Francisco Goya