Fearless conversations with friendly people.

Philosophy, poetry, technology, history...

Reignite your love of learning, reading, and discussion!

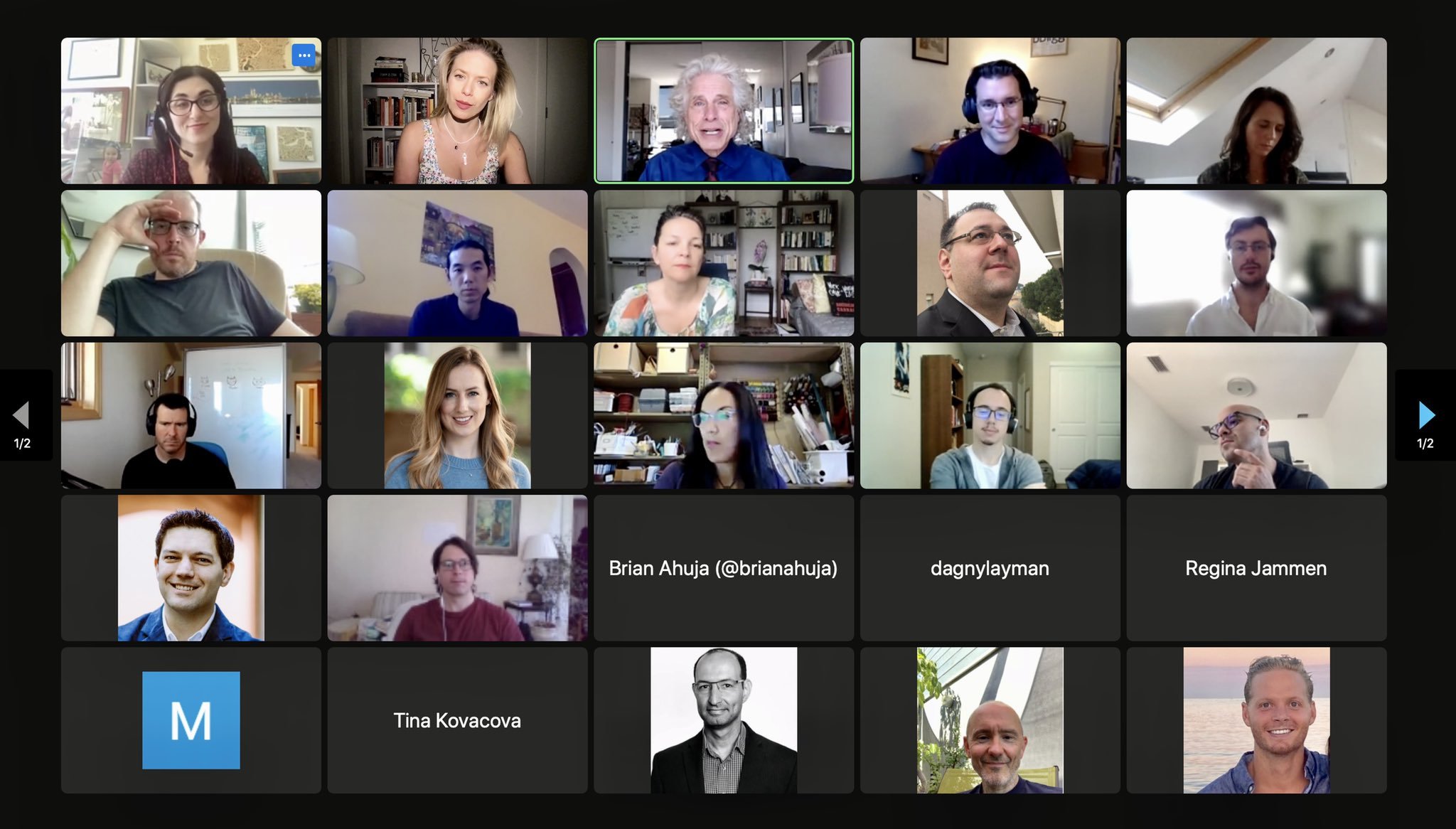

Join public and members only salons online and offline.

Or start hosting your own.

Interintellect is a curated marketplace of high-quality events hosted by intellectual seekers from all walks of life. Attend public salons, join our membership tier for free tickets and offline socials around the world, or start hosting your own events about your favorite questions and ideas! Tapping into the universe of Interintellect helps you discover the intellectual leaders of the future, grow your personal audience, increase your creator income, make lifelong like-minded friends all while discussing the most important topics of today in laid-back facilitated spaces.

.jpg)

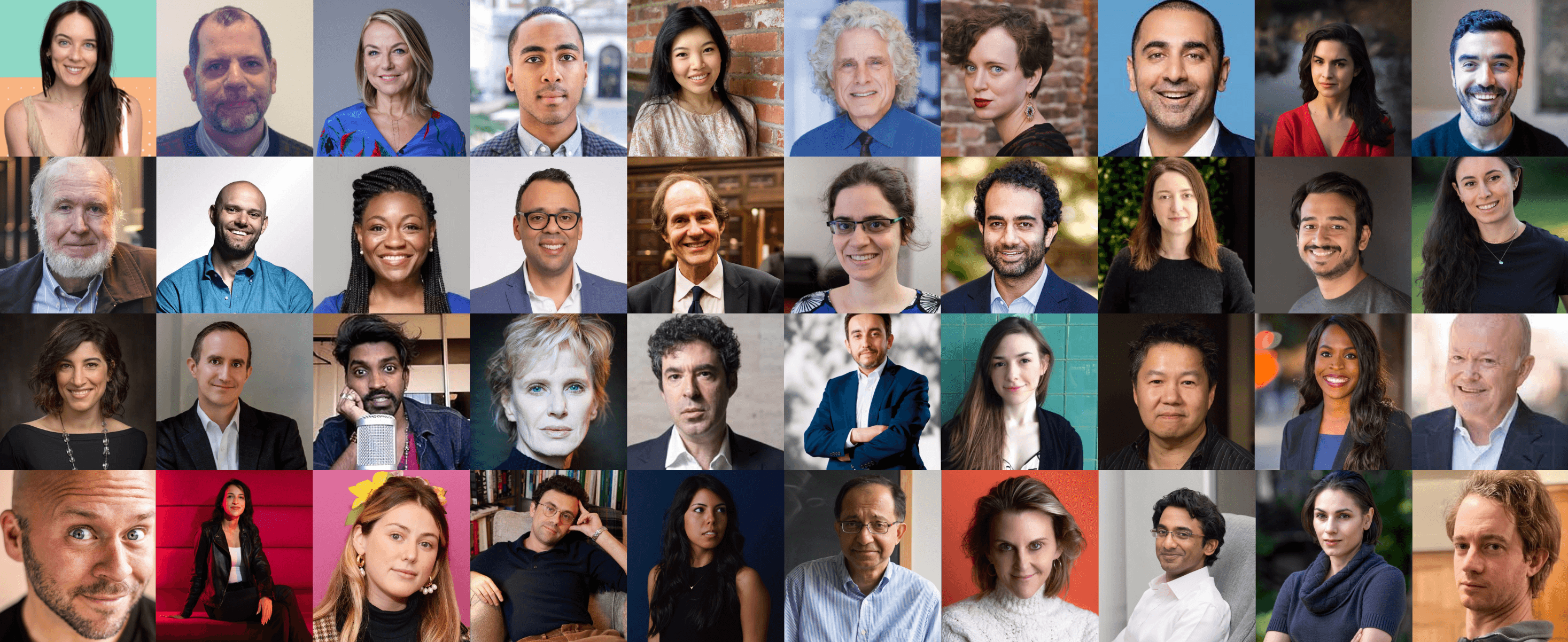

Proudly Welcoming On Our Platform